Fred Rogers

Fred Rogers | |

|---|---|

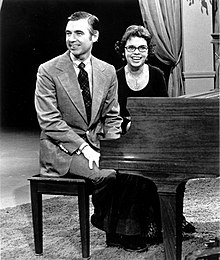

Rogers in 1982 | |

| Born | Fred McFeely Rogers March 20, 1928 Latrobe, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | February 27, 2003 (aged 74) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Unity Cemetery, Latrobe, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Other names | Mister Rogers |

| Education | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1951–2003 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (2002) |

| Official name | Fred McFeely Rogers (1928–2003) |

| Type | Roadside |

| Designated | June 11, 2016 |

| Signature | |

Fred McFeely Rogers (March 20, 1928 – February 27, 2003), better known as Mister Rogers, was an American television host, author, producer, and Presbyterian minister.[1] He was the creator, showrunner, and host of the preschool television series Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, which ran from 1968 to 2001.

Born in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, Rogers earned a bachelor's degree in music from Rollins College in 1951. He began his television career at NBC in New York City, returning to Pittsburgh in 1953 to work for children's programming at NET (later PBS) television station WQED. He graduated from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary with a bachelor's degree in divinity in 1962 and became a Presbyterian minister in 1963. He attended the University of Pittsburgh's Graduate School of Child Development, where he began his thirty-year collaboration with child psychologist Margaret McFarland. He also helped develop the children's shows The Children's Corner (1955) for WQED in Pittsburgh and Misterogers (1963) in Canada for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. In 1968, he returned to Pittsburgh and adapted the format of his Canadian series to create Mister Rogers' Neighborhood. It ran for 33 years and was critically acclaimed for focusing on children's emotional and physical concerns, such as death, sibling rivalry, school enrollment, and divorce.

Rogers died of stomach cancer in 2003, aged 74. His work in children's television has been widely lauded, and he received more than forty honorary degrees and several awards, including a Lifetime Achievement Emmy in 1997 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002. He was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1999. Rogers influenced many writers and producers of children's television shows, and his broadcasts provided comfort during tragic events, even after his death.

Early life

Rogers was born in 1928, at 705 Main Street in Latrobe, Pennsylvania.[2] His father, James Hillis Rogers, was "a very successful businessman"[3] who was president of the McFeely Brick Company, one of Latrobe's most prominent businesses. His mother, Nancy (née McFeely), knitted sweaters for American soldiers from western Pennsylvania who were fighting in Europe and regularly volunteered at the Latrobe Hospital. Initially dreaming of becoming a doctor, she settled for a life of hospital volunteer work. Her father, Fred Brooks McFeely, after whom Rogers was named, was an entrepreneur.[4]

Rogers grew up in a large three-story brick house at 737 Weldon Street in Latrobe.[2][5] He had a sister, Elaine, whom the Rogerses adopted when he was eleven years old.[5] Rogers spent much of his childhood alone, playing with puppets, and also spent time with his grandfather. He began playing the piano when he was five.[6] Through an ancestor who immigrated from Germany to the U.S., Johannes Meffert (born 1732), Rogers is the sixth cousin of actor Tom Hanks, who portrays him in the film A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood (2019).[7]

Rogers had a difficult childhood. Shy, introverted, and overweight, he was frequently homebound after suffering bouts of asthma.[3] He was bullied as a child for his weight and called "Fat Freddy".[8] According to Morgan Neville, director of the 2018 documentary Won't You Be My Neighbor?, Rogers had a "lonely childhood ... I think he made friends with himself as much as he could. He had a ventriloquist dummy, he had [stuffed] animals, and he would create his own worlds in his childhood bedroom".[8]

Rogers attended Latrobe High School, where he overcame his shyness.[9] "It was tough for me at the beginning," Rogers told NPR's Terry Gross in 1984, "and then I made a couple friends who found out that the core of me was okay. And one of them was ... the head of the football team".[10] Rogers became president of the student council, a member of the National Honor Society, and editor-in-chief of the school yearbook.[9] He registered for the draft in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, in 1948 at age 20, where he was classified 1-A (available for military service);[11] however, his status was changed to unqualified for military service following an Armed Forces physical on October 12, 1950.[11] He attended Dartmouth College for one year before transferring to Rollins College,[6] where he graduated magna cum laude[4] in 1951 with a Bachelor of Music.[12]

He then attended Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, from which he graduated magna cum laude in 1962 with a Bachelor of Divinity, and was ordained a Presbyterian minister by the Pittsburgh Presbytery of the United Presbyterian Church in 1963.[13][12][14] His work as an ordained minister, rather than to pastor a church, was to minister to children and their families through television. He regularly appeared before church officials to maintain his ordination.[15]

Career

Early work

Rogers wanted to enter seminary after college,[16] but instead chose to go into the nascent medium of television after experiencing TV at his parents' home in 1951, during his senior year at Rollins College.[17] In a CNN interview, he said, "I went into television because I hated it so, and I thought there's some way of using this fabulous instrument to nurture those who would watch and listen".[18][note 1] After graduating in 1951, he worked at NBC in New York City as floor director of Your Hit Parade, The Kate Smith Hour, and Gabby Hayes's children's show, and as an assistant producer of The Voice of Firestone.[21][22][23]

In 1953, Rogers returned to Pittsburgh to work as a program developer at public television station WQED. Josie Carey worked with him to develop the children's show The Children's Corner, which Carey hosted. Rogers worked off-camera to develop puppets, characters, and music for the show. He used many puppet characters developed during this time, such as Daniel the Striped Tiger (named after WQED's station manager, Dorothy Daniel, who gave Rogers a tiger puppet before the show's premiere),[24] King Friday XIII, Queen Sara Saturday (named after Rogers' wife),[25] X the Owl, Henrietta, and Lady Elaine, in his later work.[26][27] Children's television entertainer Ernie Coombs was an assistant puppeteer.[28] The Children's Corner won a Sylvania Award for best locally produced children's programming in 1955 and was broadcast nationally on NBC.[29][30][31] While working on the show, Rogers attended Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and was ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1963. He also attended the University of Pittsburgh's Graduate School of Child Development,[31][32] where he began working with child psychologist Margaret McFarland—who, according to Rogers' biographer Maxwell King, became his "key advisor and collaborator" and "child-education guru".[33] Much of Rogers' "thinking about and appreciation for children was shaped and informed" by McFarland.[32] She was his consultant for most of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood's scripts and songs for 30 years.[33]

In 1963, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in Toronto contracted Rogers to come to Toronto to develop and host the 15-minute black-and-white children's program Misterogers; it lasted from 1963 to 1967.[28][34] It was the first time Rogers appeared on camera. CBC's children's programming head Fred Rainsberry insisted on it, telling Rogers, "Fred, I've seen you talk with kids. Let's put you yourself on the air".[35] Coombs joined Rogers in Toronto as an assistant puppeteer.[28] Rogers also worked with Coombs on the children's show Butternut Square from 1964 to 1967. Rogers acquired the rights to Misterogers in 1967 and returned to Pittsburgh with his wife, two young sons, and the sets he developed, despite a potentially promising career with CBC and no job prospects in Pittsburgh.[36][37] On Rogers' recommendation, Coombs remained in Toronto and became Rogers' Canadian equivalent of an iconic television personality, creating the children's program Mr. Dressup, which ran from 1967 to 1996.[38] Rogers' work for CBC "helped shape and develop the concept and style of his later program for the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the U.S."[39]

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood (also called the Neighborhood), a half-hour educational children's program starring Rogers, began airing nationally in 1968 and ran for 895 episodes.[41] It was videotaped at WQED in Pittsburgh and broadcast by National Educational Television (NET), which later became the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS).[42][43] Its first season had 180 black-and-white episodes. Each subsequent season, filmed in color and funded by PBS, the Sears-Roebuck Foundation, and other charities, consisted of 65 episodes.[44][45] By the time it ended production in December 2000, its average rating was about 0.7% of television households or 680,000 homes, and it aired on 384 PBS stations. At its peak in 1985–1986, its ratings were 2.1%, or 1.8 million homes.[46][47] The last original episode aired in 2001, but PBS continued to air reruns, and by 2016 it was the third-longest-running program in PBS history.[45][48]

Many of the sets and props in Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, like the trolley, the sneakers, and the castle, were created for Rogers' show in Toronto by CBC designers and producers. The program also "incorporated most of the highly imaginative elements that later became famous",[49] such as its slow pace and its host's quiet manner.[49][50] The format of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood "remained virtually unchanged" for the entire run of the program.[51] Every episode begins with a camera's-eye view of a model of a neighborhood, then panning in closer to a representation of a house while a piano instrumental of the theme song, "Won't You be My Neighbor?", performed by music director Johnny Costa and inspired by a Beethoven sonata, is played.[52] The camera zooms in to a model representing Mr. Rogers' house, then cuts to the house's interior and pans across the room to the front door, which Rogers opens as he sings the theme song to greet his visitors while changing his suit jacket to a cardigan (knitted by his mother)[53] and his dress shoes to sneakers, "complete with a shoe tossed from one hand to another".[54] The episode's theme is introduced, and Mr. Rogers leaves his home to visit another location, the camera panning back to the neighborhood model and zooming in to the new location as he enters it. Once this segment ends, Mr. Rogers leaves and returns to his home, indicating that it is time to visit the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. Mr. Rogers proceeds to the window seat by the trolley track and sets up the action there as the Trolley comes out. The camera follows it down a tunnel in the back wall of the house as it enters the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. The stories and lessons take place over a week's worth of episodes and involve puppets and human characters. The end of the visit occurs when the Trolley returns to the same tunnel from which it emerged, reappearing in Mr. Rogers' home. He then talks to the viewers before concluding the episode. He often feeds his fish, cleans up any props he has used, and returns to the front room, where he sings the closing song while changing back into his dress shoes and jacket. He exits the front door as he ends the song, and the camera zooms out of his home and pans across the neighborhood model as the episode ends.[note 2]

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood emphasized young children's social and emotional needs, and unlike another PBS show, Sesame Street, which premiered in 1969, did not focus on cognitive learning.[55] Writer Kathy Merlock Jackson said, "While both shows target the same preschool audience and prepare children for kindergarten, Sesame Street concentrates on school-readiness skills while Mister Rogers Neighborhood focuses on the child's developing psyche and feelings and sense of moral and ethical reasoning".[56] The Neighborhood also spent fewer resources on research than Sesame Street, but Rogers used early childhood education concepts taught by his mentor Margaret McFarland, Benjamin Spock, Erik Erikson, and T. Berry Brazelton in his lessons.[57] As The Washington Post noted, Rogers taught young children about civility, tolerance, sharing, and self-worth "in a reassuring tone and leisurely cadence".[58] He tackled difficult topics such as the death of a family pet, sibling rivalry, the addition of a newborn into a family, moving and enrolling in a new school, and divorce.[58] For example, he wrote a special segment that dealt with the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy that aired on June 7, 1968, two days after the assassination occurred.[59]

According to King, the process of putting each episode of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood together was "painstaking"[60] and Rogers' contribution to the program was "astounding". Rogers wrote and edited all the episodes, played the piano and sang for most of the songs, wrote 200 songs and 13 operas, created all the characters (both puppet and human), played most of the significant puppet roles, hosted every episode, and produced and approved every detail of the program.[61] The puppets created for the Neighborhood of Make-Believe "included an extraordinary variety of personalities".[62] They were simple puppets but "complex, complicated, and utterly honest beings".[63] In 1971, Rogers formed Family Communications, Inc. (FCI, now Fred Rogers Productions), to produce the Neighborhood, other programs, and non-broadcast materials.[64][65]

In 1975, Rogers stopped producing Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood to focus on adult programming. Reruns of the Neighborhood continued to air on PBS.[66] King reports that the decision caught many of his coworkers and supporters "off guard".[67] Rogers continued to confer with McFarland about child development and early childhood education, however.[68] In 1979, after an almost five-year hiatus, Rogers returned to producing the Neighborhood; King calls the new version "stronger and more sophisticated than ever".[69] King writes that by the program's second run in the 1980s, it was "such a cultural touchstone that it had inspired numerous parodies",[19] most notably Eddie Murphy's parody on Saturday Night Live in the early 1980s.[19]

Rogers retired from producing the Neighborhood in 2001 at age 73, although reruns continued to air. He and FCI had been making about two or three weeks of new programs per year for many years, "filling the rest of his time slots from a library of about 300 shows made since 1979".[47] The final original episode of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood aired on August 31, 2001.[70]

Other work and appearances

In 1969, Rogers testified before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Communications, which was chaired by Democratic Senator John Pastore of Rhode Island. U.S. President Lyndon Johnson had proposed a $20 million bill for the creation of PBS before he left office, but his successor, Richard Nixon, wanted to cut the funding to $10 million.[71] Even though Rogers was not yet nationally known, he was chosen to testify because of his ability to make persuasive arguments and to connect emotionally with his audience. The clip of Rogers' testimony, which was televised and has since been viewed by millions of people on the internet, helped to secure funding for PBS for many years afterward.[72][73] According to King, Rogers' testimony was "considered one of the most powerful pieces of testimony ever offered before Congress, and one of the most powerful pieces of video presentation ever filmed".[74] It brought Pastore to tears and also, according to King, has been studied by public relations experts and academics.[74] Congressional funding for PBS increased from $9 million to $22 million.[71] In 1970, Nixon appointed Rogers as chair of the White House Conference on Children and Youth.[75][note 3]

In 1978, while on hiatus from Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, Rogers wrote, produced, and hosted a 30-minute interview program for adults on PBS called Old Friends ... New Friends.[77][78] It lasted 20 episodes. Rogers' guests included Hoagy Carmichael, Helen Hayes, Milton Berle, Lorin Hollander, poet Robert Frost's daughter Lesley, and Willie Stargell.[77][79]

In September 1987, Rogers visited Moscow to appear as the first guest on the long-running Soviet children's TV show Good Night, Little Ones! with host Tatyana Vedeneyeva.[80] The appearance was broadcast in the Soviet Union on December 7, coinciding with the Washington Summit meeting between Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. President Ronald Reagan in Washington, D.C.[81] Vedeneyeva visited the set of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood in November. Her visit was taped and later aired in March 1988 as part of Rogers' program.[82] In 1994, Rogers wrote, produced, and hosted a special for PBS called Fred Rogers' Heroes, which featured interviews and portraits of four people from across the country who were having a positive impact on children and education.[83][84] The first time Rogers appeared on television as an actor, and not himself, was in a 1996 episode of Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman, playing a preacher.[6]

Rogers gave "scores of interviews".[85] Though reluctant to appear on television talk shows, he would usually "charm the host with his quick wit and ability to ad-lib on a moment's notice".[86] Rogers was "one of the country's most sought-after commencement speakers",[87] making over 150 speeches.[85] His friend and colleague David Newell reported that Rogers would "agonize over a speech",[88] and King reported that Rogers was at his least guarded during his speeches, which were about children, television, education, his view of the world, how to make the world a better place, and his quest for self-knowledge. His tone was quiet and informal but "commanded attention".[85] In many speeches, including the ones he made accepting a Lifetime Achievement Emmy in 1997,[89] for his induction into the Television Hall of Fame in 1999,[87] and his final commencement speech at Dartmouth College in 2002, he instructed his audiences to remain silent and think for a moment about someone who had a good influence on them.[90]

Personal life

Rogers met Sara Joanne Byrd (called "Joanne") from Jacksonville, Florida, while attending Rollins College. They were married from 1952 until he died in 2003. They had two sons, James and John.[91][92] Joanne Rogers was "an accomplished pianist"[93] who, like Fred, earned a Bachelor of Music from Rollins, and went on to earn a Master of Music from Florida State University. She performed publicly with her college classmate, Jeannine Morrison, from 1976 to 2008.[93][94] According to biographer Maxwell King, Rogers' close associates said he was "absolutely faithful to his marriage vows".[95][96]

Rogers was red-green color-blind.[89][97] He became a pescatarian in 1970, after the death of his father, and a vegetarian in the early 1980s,[98] saying he "couldn't eat anything that had a mother".[99] He became a co-owner of Vegetarian Times in the mid-1980s[99] and said in one issue, "I love tofu burgers and beets".[100] He told Vegetarian Times that he became a vegetarian for both ethical and health reasons.[100] According to his biographer Maxwell King, Rogers also signed his name to a statement protesting wearing animal furs.[99]

Rogers was a registered Republican, but according to Joanne Rogers, he was "very independent in the way he voted", choosing not to talk about politics because he wanted to be impartial.[101]

Rogers was a Presbyterian, and many of the messages he expressed in Mister Rogers' Neighborhood were inspired by the core tenets of Christianity. Rogers rarely spoke about his faith on air; he believed that teaching through example was as powerful as preaching. He said, "You don't need to speak overtly about religion in order to get a message across". According to writer Shea Tuttle, Rogers considered his faith a fundamental part of his personality and "called the space between the viewer and the television set 'holy ground'". He also studied Catholic mysticism, Judaism, Buddhism, and other faiths and cultures.[99][102] King called him "that unique television star with a real spiritual life",[102] emphasizing the values of patience, reflection, and "silence in a noisy world".[99]

King reported that despite Rogers' family's wealth, he cared little about making money, and lived frugally, especially as he and his wife grew older.[103][104] King reported that Rogers' relationship with his young audience was important to him. For example, since hosting Misterogers in Canada, he answered every letter sent to him by hand. After Mister Rogers' Neighborhood began airing in the U.S., the letters increased in volume, and he hired staff member and producer Hedda Sharapan to answer them, but he read, edited, and signed each one. King wrote that Rogers saw responding to his viewers' letters as "a pastoral duty of sorts".[105]

The New York Times called Rogers "a dedicated lap-swimmer",[87] and Tom Junod, author of "Can You Say ... Hero?", the 1998 Esquire profile of Rogers, said, "Nearly every morning of his life, Mister Rogers has gone swimming".[89] Rogers began swimming when he was a child at his family's vacation home outside Latrobe, where they owned a pool, and during their winter trips to Florida. King wrote that swimming and playing the piano were "lifelong passions" and that "both gave him a chance to feel capable and in charge of his destiny",[106] and that swimming became "an important part of the strong sense of self-discipline he cultivated". Rogers swam daily at the Pittsburgh Athletic Association, after waking every morning between 4:30 and 5:30 A.M. to pray and to "read the Bible and prepare himself for the day".[107] He did not smoke or drink.[87] According to Junod, he did nothing to change his weight from the 143 pounds (65 kg) he weighed for most of his adult life; by 1998, this also included napping daily, going to bed at 9:30 P.M., and sleeping eight hours per night without interruption. Junod said Rogers saw his weight "as a destiny fulfilled", telling Junod, "the number 143 means 'I love you.' It takes one letter to say 'I' and four letters to say 'love' and three letters to say 'you'".[89]

Sexuality

According to biographer Michael Long in a 2016 HuffPost essay, Rogers' sexuality had long been a topic of curiosity due to his lack of traditional machismo.[108][109] The 2018 documentary Won't You Be My Neighbor? briefly addresses the subject, including an interview with François Clemmons, the gay actor who played Officer Clemmons on Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, who denied that Rogers was gay, saying that if he had a "gay vibe" he would have noticed it.[108]

In 2019, social media users shared an excerpt from the 2018 biography The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers, which recounts Rogers telling openly gay friend Dr. William Hirsch that he "must be right smack in the middle" of a one-to-ten sexuality scale, because "I have found women attractive, and I have found men attractive."[108][110] This led some social media users to suggest that Rogers may have been bisexual.[108][110] Long noted in his essay that there is no evidence that Rogers ever had sexual relations with men.[108][109]

Death and memorials

After Rogers' retirement in 2001, he remained busy working with FCI, studying religion and spirituality, making public appearances, traveling, and working on a children's media center named after him at Saint Vincent College in Latrobe with Archabbot Douglas Nowicki, chancellor of the college.[111] By the summer of 2002, his chronic stomach pain became severe enough for him to see a doctor about it, and in October 2002, he was diagnosed with stomach cancer.[112] He delayed treatment until after he served as Grand Marshal of the 2003 Rose Parade, with Art Linkletter and Bill Cosby, in January.[113] On January 6, Rogers underwent stomach surgery. He died less than two months later, on February 27, 2003, less than a month short of his 75th birthday[114][115] at his home in Pittsburgh, with his wife of 50 years, Joanne, at his side. While comatose shortly before his death, he received the last rites of the Catholic Church from Archabbot Nowicki.[6][115][116]

The following day, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette covered Rogers' death on the front page and dedicated an entire section to his death and impact.[115] The newspaper also reported that by noon, the internet "was already full of appreciative pieces" by parents, viewers, producers, and writers.[117] Rogers' death was widely lamented. Most U.S. metropolitan newspapers ran his obituary on their front page and some dedicated entire sections to coverage of his death.[118] WQED aired programs about Rogers the evening he died; the Post-Gazette reported that the ratings for their coverage were three times higher than their normal ratings.[118] That same evening, Nightline on ABC broadcast a rerun of a recent interview with Rogers; the program got the highest ratings of the day, beating the February average ratings of Late Show with David Letterman and The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.[118] On March 4, the U.S. House of Representatives unanimously passed a resolution honoring Rogers sponsored by Representative Mike Doyle from Pennsylvania.[119]

On March 1, 2003, a private funeral was held for Rogers in Unity Chapel, which was restored by Rogers' father, at Unity Cemetery in Latrobe. About 80 relatives, co-workers, and close friends attended the service, which "was planned in great secrecy so that those closest to him could grieve in private".[120] Reverend John McCall, pastor of the Rogers family's church, Sixth Presbyterian Church in Squirrel Hill, gave the homily; Reverend William Barker, a retired Presbyterian minister who was a "close friend of Mr. Rogers and the voice of Mr. Platypus on his show",[120] read Rogers' favorite Bible passages. Rogers was interred at Unity Cemetery in his hometown of Latrobe, Pennsylvania, in a mausoleum owned by his mother's family.[120][121]

On May 3, 2003, a public memorial was held at Heinz Hall in Pittsburgh. According to the Post-Gazette, 2,700 people attended. Violinist Itzhak Perlman, cellist Yo-Yo Ma (via video), and organist Alan Morrison performed in honor of Rogers. Barker officiated the service; also in attendance were Pittsburgh philanthropist Elsie Hillman, former Good Morning America host David Hartman, The Very Hungry Caterpillar author Eric Carle, and Arthur creator Marc Brown. Businesswoman and philanthropist Teresa Heinz, PBS President Pat Mitchell, and executive director of The Pittsburgh Project Saleem Ghubril gave remarks.[122] Jeff Erlanger, who at age 10 appeared on Mister Rogers' Neighborhood in 1981 to explain his electric wheelchair, also spoke.[123] The memorial was broadcast several times on Pittsburgh television stations and websites throughout the day.[124]

Legacy

When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, "Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping." To this day, especially in times of "disaster", I remember my mother's words and I am always comforted by realizing that there are still so many helpers—so many caring people in this world.

—Fred Rogers[125]

Whenever a great tragedy strikes—war, famine, mass shootings, or even an outbreak of populist rage—millions of people turn to Fred's messages about life. Then the web is filled with his words and images. With fascinating frequency, his written messages and video clips surge across the internet, reaching hundreds of thousands of people who, confronted with a tough issue or ominous development, open themselves to Rogers' messages of quiet contemplation, of simplicity, of active listening and the practice of human kindness.

—Rogers biographer Maxwell King[126]

Marc Brown, creator of another PBS children's show, Arthur, considered Rogers both a friend and "a terrific role model for how to use television and the media to be helpful to kids and families".[127] Josh Selig, creator of Wonder Pets, credits Rogers with influencing his use of structure and predictability, and his use of music, opera, and originality.[128]

Rogers inspired Angela Santomero, co-creator of the children's television show Blue's Clues, to earn a degree in developmental psychology and go into educational television.[129] She and the other producers of Blue's Clues used many of Rogers' techniques, such as using child developmental and educational research and having the host speak directly to the camera and transition to a make-believe world.[130] In 2006, three years after Rogers' death and the end of production of Blue's Clues, the Fred Rogers Company contacted Santomero to create a show that would promote Rogers' legacy.[129] In 2012, Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood, with characters from and based upon Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, premiered on PBS.[131]

Rogers' style and approach to children's television and early childhood education also "begged to be parodied".[132] Comedian Eddie Murphy parodied Mister Rogers' Neighborhood on Saturday Night Live during the 1980s.[19][133] Rogers told interviewer David Letterman in 1982 that he believed parodies like Murphy's were done "with kindness in their hearts".[134]

Video of Rogers' 1969 testimony in defense of public programming has experienced a resurgence since 2012, going viral at least twice. It first resurfaced after then presidential candidate Mitt Romney suggested cutting funding for PBS.[135][136] In 2017, video of the testimony again went viral after President Donald Trump proposed defunding several arts-related government programs including PBS and the National Endowment for the Arts.[135][137]

A roadside Pennsylvania Historical Marker dedicated to Rogers to be installed in Latrobe was approved[138] by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission on March 4, 2014.[139] It was installed on June 11, 2016, with the title "Fred McFeely Rogers (1928–2003)".[140]

Won't You Be My Neighbor? director Morgan Neville's 2018 documentary about Rogers' life, grossed over $22 million and became the top-grossing biographical documentary ever produced, the highest-grossing documentary in five years, and the twelfth-largest-grossing documentary ever made.[141][142] The 2019 drama film A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood tells the story of Rogers and his television series, with Tom Hanks portraying Rogers.

According to Caitlin Gibson of The Washington Post, Rogers became a source for parenting advice; she called him "a timeless oracle against a backdrop of ever-shifting parenting philosophies and cultural trends".[141] Robert Thompson of Syracuse University noted that Rogers "took American childhood—and I think Americans in general—through some very turbulent and trying times",[133] from the Vietnam War and the assassination of Robert Kennedy in 1968 to the 9/11 attacks in 2001. According to Asia Simone Burns of National Public Radio, in the years following the end of production on Mister Rogers' Neighborhood in 2001 and his death in 2003, Rogers became "a source of comfort, sometimes in the wake of tragedy".[133] Burns has said Rogers' words of comfort "began circulating on social media"[133] following tragedies such as the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012, the Manchester Arena bombing in Manchester, England, in 2017, and the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, in 2018.

Awards and honors

| Year | Honor | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Outstanding Rollins Alumnus of 1970 | Given by Rollins College. | [143] |

| 1975 | Ralph Lowell Award | Given by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting in recognition of "outstanding contributions and achievements to public television". | [144] |

| 1977 | Myrtle Wreath Award | Awarded for "outstanding contributions to the community" | [145] |

| 1977 | Other's Award | Given at the 13th Annual Civic Luncheon of the Salvation Army Association of Greater Pittsburgh. Awarded for humanitarianism. | [146][147] |

| 1978 | Distinguished Alumnus Award | Given by Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. | [148] |

| 1978 | 1977-78 Lay Leader Award | Given by the Three Rivers Chapter, University of Pittsburgh, Phi Delta Kappa fraternity | [149] |

| 1978 | Gabriel awardee | Given by the Catholic Broadcasting Association | [150] |

| 1981 | Distinguished Communications Recognition Award | Awarded at the 12th national Abe Lincoln Awards banquet for his work in children's television. | [151] |

| 1982 | Media Arts Award | Given as part of the third annual Governor's Day Awards in the Arts. | [152] |

| 1986 | CINE Golden Eagle Award | Awarded for Rogers' educational special for children "Let's Talk About Going to the Doctor." | [153] |

| 1987 | CINE Golden Eagle Award | Awarded for Rogers' educational special for children "Mister Rogers Talks With Children About Saying Goodbye to Friends." | [153] |

| 1987 | Honorary member, Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia | Fraternity for male musicians who have adopted music as a career. | [154] |

| 1988 | Immaculata Medal | Given by Immaculata College. It is the college's highest honor. | [155][156] |

| 1989 | 1989 Man of the Year | Named by the Vectors/Pittsburgh. | [157] |

| 1990 | Gold Medal for Distinguished Achievement | Given by the Pennsylvania Society, which recognizes Pennsylvanians who made significant contributions to the Commonwealth. The Society donated $25,000 to the McFarland Fund of the Pittsburgh Foundation (named after Margaret McFarland) in Rogers' honor. | [158] |

| 1991 | Pittsburgh Penguins Celebrity Captain | Part of the National Hockey League (NHL)'s 75th anniversary. Rogers was one of 12 celebrity captains to be selected for the 1992 Pro Set Platinum collection. | [159][160] |

| 1991 | Rollins College Walk of Fame | Honored by Rollins College. | [143] |

| 1992 | Comenius Medallion | Given by Moravian College along with an honorary degree. It is the college's highest honor. | [161] |

| 1992 | Peabody Award | Awarded "in recognition of 25 years of beautiful days in the neighborhood".[162] | [163] |

| 1994 | President's Distinguished Service Medal | Given by Colgate Rochester Divinity School. Rogers spoke at the commencement of the school's Bexley–Hall–Crozer Theological Seminary on the date of receipt. The award is the school's equivalent of an honorary degree. | [164][165] |

| 1995 | National Patron, Delta Omicron | Awarded by the international professional music fraternity to musicians who have attained "a national reputation in his or her field".[166] | [167] |

| 1995 | Joseph F. Mulach Jr. Award | Presented by the Vocational Rehabilitation Center board of directors in Pittsburgh. The award is given to a person who made major improvements to the quality of life of the disabled. | [168] |

| 1997 | Lifetime Achievement Emmy | Awarded "for giving generation upon generation of children confidence in themselves, for being their friend, for telling them again and again and again that they are special and that they have worth."[169] | [87] |

| 1997 | Television Critics Association Career Achievement | Awarded for Rogers' "longevity and influence." | [170][171] |

| 1998 | Hollywood Walk of Fame star | Located at 6600 Hollywood Blvd. | [172] |

| 1999 | Television Hall of Fame inductee | Jeff Erlanger appeared as a surprise guest during the ceremony. | [173] |

| 1999 | Pennsylvania Founder's Award | The award was created in 1997 to recognize a Pennsylvanian who has made major contributions to their state. Governor Tom Ridge presented the award. | [174] |

| 2000 | Presidential Medal of Honor | Presented by St. Vincent College. Rogers was a guest speaker for the college's 154th commencement on the date of receipt. | [175] |

| 2001 | Fred Rogers Award | Presented by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Rogers was the first recipient of this award. | [176] |

| 2002 | Elsie Award | Awarded for community service. | [177] |

| 2002 | Presidential Medal of Freedom | The highest American civilian honor; awarded by President George W. Bush. | [178] |

| 2002 | Common Wealth Award | Given by PNC Financial Services, "celebrating the best of human achievement". | [180] |

| 2003 | International Astronomical Union asteroid designation | Asteroid 26858 Misterrogers named in Rogers' honor, discovered by Eleanor Helin in 1993. | [181][182] |

| 2006 | Television Hall of Fame inductee | Awarded by the Online Film & Television Association. In 2010, Mister Rogers' Neighborhood was inducted into the Hall of Fame. | [183][184] |

| 2008 | "Sweater Day" | Tribute to Rogers on what would have been his 80th birthday (March 20) by FCI. People worldwide were encouraged to wear a sweater honoring Rogers' legacy and the final event in a six-day celebration in Pittsburgh. | [185][186] |

| 2015 | "Sweater drive" | Rogers honored by the Altoona Curve, a Double-A affiliate of the Pittsburgh Pirates. The team wore commemorative jerseys that featured a printed facsimile of Rogers' cardigan and tie ensemble, which were then auctioned off, with the proceeds going to the local PBS station, WPSU-TV. | [187] |

| 2018 | First-class/Forever postage stamp issued by the U.S. Postal Service | Dedicated on March 23 at WQED. | [188][189] |

| 2018 | Google Doodle | In honor of the 51st anniversary of the premiere of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood (September 21). Created in collaboration with Fred Rogers Productions, The Fred Rogers Center, and BixPix Entertainment. | [190][191] |

| 2019 | Unforgettable Nonfiction Subject of 2018 | Awarded by Cinema Eye Honors for being a "notable and significant nonfiction film subject" in Won't You Be My Neighbor? | [192] |

| 2021 | Grammy Award | Awarded posthumously by The Recording Academy for Best Historical Album for It's Such a Good Feeling: The Best of Mister Rogers. Fred Rogers and Michael Graves, mastering engineers; Lee Lodyga and Cheryl Pawelski, compilation producers. | [193] |

Museum exhibits

- Smithsonian Institution permanent collection. In 1984, Rogers donated one of his sweaters to the Smithsonian.[23][194]

- Children's Museum of Pittsburgh. Exhibit created by Rogers and FCI in 1998. It attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors over ten years. It included, from Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, one of his sweaters, a pair of his sneakers, original puppets from the program, and photographs of Rogers. The exhibit traveled to children's museums throughout the country for eight years until it was given to the Louisiana Children's Museum in New Orleans as a permanent exhibit to help them recover from Hurricane Katrina in 2005. In 2007, the Children's Museum of Pittsburgh created a traveling exhibit based on the factory tours featured in episodes of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.[195][196][197]

- Heinz History Center permanent collection (2018). In honor of the 50th anniversary of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood and what would have been Rogers' 90th birthday.[198] Exhibits include the iconic King Friday's blue castle, the Owl's tree and a tricycle ridden by courier Mr. McFeely.[199]

- Louisiana Children's Museum. The museum contains an exhibit of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, which debuted in 2007. The Children's Museum of Pittsburgh donated the exhibit.[195]

- Fred Rogers Exhibit. The Exhibit displays the life, career, and legacy of Rogers and includes photos, artifacts from Mister Rogers' Neighborhood and clips of the program and interviews featuring Rogers. It is located at the Fred Rogers Center.[200]

Art pieces

Several pieces of art are dedicated to Rogers throughout Pittsburgh, including an eleven-foot (3.4 m) tall, 7,000-pound (3,200 kg) bronze statue of him in the North Shore neighborhood. In the Oakland neighborhood, his portrait is included in the Martin Luther King Jr. and "Interpretations of Oakland" murals. A dinosaur statue titled "Fredasaurus Rex Friday XIII" originally stood in front of the WQED building and, as of 2014, stood in front of the building containing the Fred Rogers Company offices. There is a "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood of Make-Believe" in Idlewild Park and a kiosk of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood artifacts at Pittsburgh International Airport.[201] The Carnegie Science Center's Miniature Railroad and Village debuted a miniature recreation of Rogers' house from Mister Rogers' Neighborhood in 2005.[202] In Rogers' hometown of Latrobe, a statue of Rogers on a bench is situated in James H. Rogers Park—a park named for Rogers' father.[203] In 2021, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood—a seven-foot (2.1 m) tall, 3,000-pound (1,400 kg) bronze statue by Paul Day—was dedicated at Rollins College. The memorial depicts Rogers and Daniel Tiger speaking with a group of children and features lyrics from Mister Rogers' Neighborhood's theme on the base.[204]

Honorary degrees

Rogers has received honorary degrees from over 43 colleges and universities. After 1973, two commemorative quilts, created by two of Rogers' friends and archived at the Fred Rogers Center at St. Vincent College in Latrobe, were made out of the academic hoods he received during the graduation ceremonies.[205][206]

Note: Much of the below list is taken from "Honorary Degrees Awarded to Fred Rogers",[148] unless otherwise stated.

- Thiel College, 1969. Thiel also awards a yearly scholarship named for Rogers.[205]

- Eastern Michigan University, 1973

- Saint Vincent College, 1973

- Christian Theological Seminary, 1973

- Rollins College, 1974

- Yale University, 1974

- Chatham College, 1975[207]

- Carnegie Mellon University, 1976

- Lafayette College, 1977

- Waynesburg College, 1978

- Linfield College, 1982

- Slippery Rock State College, 1982

- Duquesne University, 1982

- Washington & Jefferson College, 1984

- University of South Carolina, 1985

- Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 1985

- Drury College, 1986[208]

- MacMurray College, 1986[209]

- Bowling Green State University, 1987[210]

- Westminster College (Pennsylvania), 1987[211]

- University of Indianapolis, 1988[212]

- University of Connecticut, 1991[213]

- Boston University, 1992[214]

- Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 1992[215]

- Moravian College, 1992[216]

- Goucher College, 1993[217]

- University of Pittsburgh, 1993[218]

- West Virginia University, 1995[219]

- North Carolina State University, 1996[220]

- Edinboro University of Pennsylvania, 1998[221]

- Marist College, 1999[222]

- Westminster Choir College, 1999[223]

- Old Dominion University, 2000[224]

- Marquette University, 2001[225]

- Middlebury College, 2001[226]

- Dartmouth College, 2002[206]

- Seton Hill University, 2003 (posthumous)[227]

- Union College, 2003 (posthumous)[228]

- Roanoke College, 2003 (posthumous)[206]

Filmography

Television

| Year | Title |

|---|---|

| 1954–1961 | The Children's Corner[229] |

| 1963–1966 | Misterogers[36] |

| 1964–1967 | Butternut Square[36] |

| 1968–2001 | Mister Rogers' Neighborhood[36] |

| 1977–1982 | Christmastime with Mister Rogers[230] |

| 1978–1980 | Old Friends ... New Friends |

| 1981 | Sesame Street[231] |

| 1988 | Good Night, Little Ones![232] |

| 1991 | Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? |

| 1994 | Mr. Dressup's 25th Anniversary |

| 1994 | Fred Rogers' Heroes[233] |

| 1996 | Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman[234] |

| 1997 | Arthur[235] |

| 1998 | Wheel of Fortune[236] |

| 2003 | 114th Annual Tournament of Roses Parade[237] |

Published works

Children's books

- Our Small World (with Josie Carey, illustrated by Norb Nathanson), 1954, Reed and Witting, OCLC 236163646

- The Elves, the Shoemaker, & the Shoemaker's Wife (illustrated by Richard Hefter), 1973, Small World Enterprises, OCLC 969517

- The Matter of the Mittens, 1973, Small World Enterprises, OCLC 983991

- Speedy Delivery (illustrated by Richard Hefter), 1973, Hubbard, OCLC 11464480

- Henrietta Meets Someone New (illustrated by Jason Art Studios), 1974, Golden Press, OCLC 950967676

- Mister Rogers Talks About, 1974, Platt & Munk, OCLC 1093164

- Time to Be Friends, 1974, Hallmark Cards, OCLC 1694547

- Everyone is Special (illustrated by Jason Art Studios), 1975, Western Publishing, OCLC 61280957

- Tell Me, Mister Rogers, 1975, Platt & Munk, OCLC 1525780

- The Costume Party (illustrated by Jason Art Studios), 1976, Golden Press, OCLC 3357187

- Planet Purple (illustrated by Dennis Hockerman), 1986, Texas Instruments, ISBN 978-0-89512-092-2

- If We Were All the Same (illustrated by Pat Sustendal), 1987, Random House, OCLC 15083194

- A Trolley Visit to Make-Believe (illustrated by Pat Sustendal), 1987, Random House, OCLC 17237650

- Wishes Don't Make Things Come True (illustrated Pat Sustendal), 1987, Random House, OCLC 15196769

- No One Can Ever Take Your Place (illustrated by Pat Sustendal), 1988, Random House, OCLC 990550735

- When Monsters Seem Real (illustrated by Pat Sustendal), 1988, Random House, OCLC 762290817

- You Can Never Go Down the Drain (illustrated by Pat Sustendal), 1988, Random House, ISBN 978-0-394-80430-9

- The Giving Box (illustrated by Jennifer Herbert), 2000, Running Press, OCLC 45616325

- Good Weather or Not (with Hedda Bluestone Sharapan, illustrated by James Mellet), 2005, Family Communications, OCLC 31597516

- Josephine the Short Neck-Giraffe, 2006, Family Communications, OCLC 1048459379

- A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood: The Poetry of Mister Rogers Neighborhood (illustrated by Luke Flowers), 2009, Quirk Books, OCLC 1042097615

- First Experiences series illustrated by Jim Judkis

- Going to Day Care, 1985, Putnam, OCLC 11397421

- The New Baby, 1985, Putnam, OCLC 11470082

- Going to the Potty, 1986, Putnam, OCLC 1123224708

- Going to the Doctor, 1986, Putnam, OCLC 12751383

- Making Friends, 1987, Putnam, OCLC 1016110382

- Moving, 1987, Putnam, OCLC 13526459

- Going to the Hospital, 1988, Putnam, OCLC 16472458

- When a Pet Dies, 1988, Putnam, OCLC 16130718

- Going on an Airplane, 1989, Putnam, OCLC 18589040

- Going to the Dentist, 1989, Putnam, OCLC 17954325

- Let's Talk About It series

- Going to the Hospital, 1977, Family Communications, OCLC 11287782

- Having an Operation, 1977, Family Communications, OCLC 11394237

- So Many Things To See!, 1977, Family Communications, OCLC 704507774

- Wearing a Cast, 1977, Family Communications, OCLC 11287804

- Adoption, 1993, Putnam, OCLC 608811678

- Divorce, 1994, Putnam, OCLC 228437876

- Extraordinary Friends, 2000, Putnam, OCLC 40838701

- Stepfamilies, 2001, Putnam, OCLC 35192315

Songbooks

- Tomorrow on the Children's Corner (with Josie Carey, illustrated by Mal Wittman), 1960, Vernon Music Corporation, OCLC 12316162

- Mister Rogers' Songbook (with Johnny Costa, illustrated by Steven Kellogg), 1970, Random House, OCLC 34224058

Books for adults

- Mister Rogers Talks to Parents, 1983, Family Communications, OCLC 704903806

- Mister Rogers' Playbook (with Barry Head, illustrated by Jamie Adams), 1986, Berkley Books, OCLC 1016158916

- Mister Rogers Talks with Families About Divorce (with Clare O'Brien), 1987, Berkley Books, OCLC 229152864

- Mister Rogers' How Families Grow (with Barry Head and Jim Prokell), 1988, Berkley Books, OCLC 20133117

- You Are Special: Words of Wisdom from America's Most Beloved Neighbor, 1994, Penguin Books, OCLC 1007556599

- Dear Mister Rogers, 1996, Penguin Books, OCLC 1084686063

- Mister Rogers' Playtime, 2001, Running Press, OCLC 48118722

- The Mister Rogers Parenting Book, 2002, Running Press, OCLC 50757046

- You are special: Neighborly Wisdom from Mister Rogers, 2002, Running Press, OCLC 50402664

- The World According to Mister Rogers, 2003, Hyperion Books, OCLC 52520625

- Life's Journeys According to Mister Rogers, 2005, Hyperion Books, OCLC 56686439

- The Mister Rogers Parenting Resource Book, 2005, Courage Books, OCLC 60452524

- Many Ways to Say I Love You: Wisdom For Parents And Children, 2019, Hachette Books, OCLC 1082231639

Discography

- Around the Children's Corner (with Josey Carey), 1958, Vernon Music Corporation, OCLC 12310040

- Tomorrow on the Children's Corner (with Josie Carey), 1959[238]

- King Friday XIII Celebrates, 1964[239]

- Won't You Be My Neighbor?, 1967[240]

- Let's Be Together Today, 1968[240]

- Josephine the Short-Neck Giraffe, 1969[240]

- You Are Special, 1969[240]

- A Place of Our Own, 1970[240]

- Come On and Wake Up, 1972[241]

- Growing, 1992[233]

- Bedtime, 1992[241]

- Won't You Be My Neighbor? (cassette and book), 1994, Hal Leonard, OCLC 36965578

- Coming and Going, 1997[242]

- It's Such a Good Feeling: The Best of Mister Rogers, 2019, Omnivore Recordings, posthumous release[243]

See also

- Won't You Be My Neighbor?, 2018 documentary

- Mister Rogers: It's You I Like, 2018 documentary

- A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, 2019 biographical drama film

- List of vegetarians

Notes

- ^ According to Mister Rogers' Neighborhood producer Hedda Sharapan, Rogers used television to communicate his message;[19] David Newell, who played Mr. McFeely on the Neighborhood, said, "Television was a vehicle for Fred, to reach children and families; it was sort of a necessary evil".[20]

- ^ See Wolfe, pp. 9–16, for a complete description of the structure of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.

- ^ See American Rhetoric.com for the transcript of Rogers's testimony.[76]

References

- ^ "Fred Rogers". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. March 16, 2020. Archived from the original on July 19, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Harpaz, Beth J. (July 18, 2018). "Mister Rogers: 'Won't you be my neighbor?' fans can check out Fred Rogers Trail". Burlington Free Press. Associated Press. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Early Life". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning & Children's Media. Archived from the original on October 15, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Woo, Elaine (February 28, 2003). "It's a Sad Day in This Neighborhood". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ a b King (2018), p. 19.

- ^ a b c d DeFranceso, Joyce (April 2003). "Remembering Fred Rogers: A Life Well-Lived: A look back at Fred Rogers' life". Pittsburgh Magazine. Archived from the original on January 3, 2005. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

- ^ Capron, Maddie; Zdanowicz, Christina (November 19, 2019). "Tom Hanks just found out he's related to Mister Rogers". CNN. Archived from the original on October 3, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ a b Breznican, Anthony (June 9, 2018). "The relics of Mister Rogers: 7 emotional items from the new film Won't You Be My Neighbor?". EW.com. Archived from the original on August 2, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Comm, Joseph A. (2015). Legendary Locals of Latrobe. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4671-0184-4.

- ^ Gross (1984), event occurs at 4.27.

- ^ a b Celebrating Mr. Rogers at the National Archives Archived January 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine U.S. National Archives. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Fred M. Rogers Receives Degree From Seminary". The Latrobe Bulletin. Vol. 60, no. 121. May 10, 1962. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ "Vol 1960–1965: Annual Catalogue of the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary". Internet Archive. Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. 1965. p. 394. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "On Sunday: Fred M. Rogers To Be Ordained". The Latrobe Bulletin. Vol. LXI, no. 145. June 8, 1963. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Burke, Daniel (November 23, 2019). "Mr. Rogers was a televangelist to toddlers". CNN.com. Archived from the original on October 3, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ Herman, Karen (October 22, 2017). "Fred Rogers: On his college years". Television Academy Interviews. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on October 13, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ Deb, Sopan (March 5, 2018). "'Mister Rogers' Neighborhood' at 50: 5 Memorable Moments". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ Schuster, Henry (February 27, 2003). "Fred and me: An appreciation". CNN.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d King, p. 266.

- ^ King, p. 265.

- ^ Hendrickson, Paul (November 18, 1982). "In the Land of Make Believe, The Real Mister Rogers". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- ^ Gross (1984), event occurs at 6.38.

- ^ a b "Highlights in the life and career of Fred Rogers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. February 27, 2003. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ Tiech, p. 10.

- ^ "Fred Rogers". Pioneers of Television. PBS.org. 2014. Archived from the original on January 7, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ "Early Years in Television". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning & Children's Media. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ Tiech, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Broughton, Irv (1986). Producers on Producing: The Making of Film and Television. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7864-1207-5.

- ^ "Sunday on the Children's Corner, Revisited". Presbyterian Historical Society. February 15, 2018. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ Schultz, Mike. "Sylvania Award". uv201.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- ^ a b "Fred Rogers Biography". Fred Rogers Productions. 2018. Archived from the original on July 29, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Flecker, Sally Ann (Winter 2014). "When Fred Met Margaret: Fred Rogers' Mentor". Pitt Med. University of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ a b King, p. 126.

- ^ King (2018), p. 145.

- ^ Roberts, Soraya (June 26, 2018). "The Fred Rogers We Know". Hazlitt Magazine. Penguin Random House. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Matheson, Sue (2016). "Good Neighbors, Moral Philosophy and the Masculine Ideal". In Merlock Jackson, Sandra; Emmanuel, Steven M. (eds.). Revisiting Mister Rogers' Neighborhood: Essays on Lessons about Self and Community. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Publishers. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4766-2341-2.

- ^ King, p. 150.

- ^ Gillmor, Don (July 11, 2018). "How Mr. Rogers and Mr. Dressup's road trip from Pittsburgh to Toronto changed children's television forever". National Post. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood and Beyond". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning & Children's Media. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- ^ "Fred Rogers Took a Stand Against Racial Inequality When He Invited a Black Character to Join Him in a Pool". Biography. May 24, 2019. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Bahr, Lindsey (September 27, 2013). "Mister Rogers pic in development with 'Little Miss Sunshine' directors". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Children's TV Host Fred Rogers Dies At 74". PBS NewsHour. February 27, 2003. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Burns, Asia Simone (February 7, 2018). "Mister Rogers Is Coming Back To Your Neighborhood, On A Stamp". NPR.org. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ King, p. 164.

- ^ a b Estrada, Louie (February 28, 2003). "Children's TV Icon Fred Rogers Dies at 74". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ DeFranceso, Joyce (April 2003). "A Life Well-Lived". Pittsburgh Magazine. Archived from the original on January 3, 2005. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ a b Montgomery, David (September 1, 2001). "For Mister Rogers, a Final Day in the Neighborhood". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Jackson, Kathy Merlock; Emmanuel, Steven M (2016). "Introduction". Revisiting Mister Rogers' Neighborhood: Essays on Lessons about Self and Community. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4766-2341-2.

- ^ a b King, p. 158.

- ^ King, p. 146.

- ^ Wolfe, Mark J. P. (2017). The World of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood. New York: Routledge Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-315-11008-0.

- ^ Woo, Elaine (February 28, 2003). "From the Archives: It's a Sad Day in This Neighborhood". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ Jackson, Christine (March 20, 2017). "The Importance of Sweaters and Sneakers in Mister Rogers' Neighborhood". Rewire.org. PBS. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Wolfe, p. 11.

- ^ King, p. 145.

- ^ Jackson, Kathy Merlock (February 17, 2016). "Social Activism for the Small Set". In Jackson, Kathy Merlock; Emmanuel, Steven M. (eds.). Revisiting Mister Rogers' Neighborhood: Essays on Lessons about Self and Community. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4766-2341-2.

- ^ King, p. 134.

- ^ a b Estrada, Louie (February 28, 2003). "Children's TV Icon Fred Rogers Dies at 74". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ King, p. 192.

- ^ King, p. 184.

- ^ King, p. 204.

- ^ King, p. 216.

- ^ King, p. 219.

- ^ "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood and Beyond". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning & Children's Media. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ Jefferson, Robin Seaton (March 23, 2017). "Siefken Heads Up Fred Rogers Company, Keeping Mister Rogers' Message Relevant For Next Generation". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 7, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- ^ King, pp. 230–231.

- ^ King, p. 231.

- ^ King, p. 240.

- ^ King, p. 243.

- ^ King, p. 338.

- ^ a b Frank, Steve (September 6, 2013). "Mr. Rogers offers timeless defense of PBS funding…in 1969". MSNBC.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2019. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ King, pp. 170–171.

- ^ King, p. 176.

- ^ a b King, p. 172.

- ^ King, p. 175.

- ^ "Mr. Fred Rogers: Senate Statement on PBS Funding". American Rhetoric.com. May 1, 1969. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ a b Neuhaus, Cable (May 15, 1978). "Fred Rogers Moves into a New Neighborhood—and So Does His Rebellious Son". People. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ King, p. 230.

- ^ King, p. 233.

- ^ Mesce, Deborah (November 20, 1987). "Beautiful Day For Mr. Rogers And Soviet Counterpart". Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Ogintz, Eileen (March 6, 1988). "Neighborhood Hero". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ Brennan, Patricia (March 6, 1988). "'Neighborhood' Detente". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ King, p. 232.

- ^ Williams, Scott (September 2, 1994). "'Mr. Rogers' Heroes' Looks at Who's Helping America's Children". AP News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c King, p. 326.

- ^ King (2018), p. 308.

- ^ a b c d e Lewis, Daniel (February 28, 2003). "Mister Rogers, TV's Friend For Children, Is Dead at 74". The New York Times. p. A00001. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ^ King (2018), p. 326.

- ^ a b c d Junod, Tom (November 1998). "Can You Say…Hero?". Esquire. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ^ "About Fred Rogers". Mister Rogers.org. The Fred Rogers Company. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ Dawn, Randee (June 12, 2018). "Fred Rogers' widow reveals the way he proposed marriage—and it's so sweet". Today.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ King (2018), p. 54.

- ^ a b Schlageter, Bill (February 3, 2016). "Children's Museum of Pittsburgh to honor Joanne Rogers with its 2016 Great Friend of Children Award". Children's Museum of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ Owen, Rob (April 9, 2002). "Music plays key role in Mrs. Rogers' relationship with husband Fred". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ King (2018), p. 208.

- ^ "Joanne Rogers, Widow Of Fred Rogers, Dies At Age 92". KDKA-TV. January 14, 2021. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ King (2018), p. 87.

- ^ Rick Sebak (host/producer) (October 19, 1987). My Interview with Fred (video clip). WQED. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d e King (2018), p. 9.

- ^ a b Obis, Paul (November 1983). "Fred Rogers: America's Favorite Neighbor". Vegetarian Times. p. 26. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ Kaufman, Amy (November 26, 2019). "How befriending Mister Rogers' widow allowed me to learn the true meaning of his legacy". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ^ a b King (2018), p. 313.

- ^ King (2018), p. 10.

- ^ King (2018), p. 336.

- ^ King (2018), p. 328.

- ^ King (2018), p. 318.

- ^ King (2018), p. 317.

- ^ a b c d e Ross, Martha (March 7, 2019). "Fred Rogers celebrated as 'bisexual icon' after his comments on sexual attraction resurface". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ a b Long, Michael (October 22, 2014). "'Wasn't He Gay?': A Revealing Question About Mister Rogers". HuffPost. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ a b Street, Mikelle (March 6, 2019). "Mr. Rogers Was Apparently Queer, Says 2015 Book". Out. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ King, pp. 338, 344.

- ^ King, pp. 343–344.

- ^ King, p. 344.

- ^ De Vinck, Christopher (February 24, 2013). "My friend, Mr. Rogers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c Owen, Rob; Vancheri, Barbara (February 28, 2003). "Fred Rogers dies at 74". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ King, p. 348.

- ^ Kalson, Sally (February 28, 2003). "Lasting connection his legacy: Children felt Mister Rogers was talking just to them". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c Simonich, Milan (March 2, 2003). "Rogers' death gets front-page headlines". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ McFeatters, Ann (March 5, 2003). "It's a beautiful day in the U.S. House as Congress honors Fred Rogers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c Rodgers-Melnick, Ann (March 2, 2003). "Friends, relatives mourn death of Mr. Rogers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ "The Grave of Mister Rogers". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ Vancheri, Barbara; Owen, Rob (May 4, 2003). "Pittsburgh bids farewell to Fred Rogers with moving public tribute". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ Vancheri, Barbara (May 4, 2003). "Memorable guest: It's you, Fred, that I like". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ Owen, Rob (May 3, 2003). "Appreciation: Mister Rogers will always be part of our neighborhood". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (April 16, 2013). "The Backstory: The Moving Mr. Rogers Clip Everyone Is Talking About". Time. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ King, p. 357.

- ^ Juul, Matt (October 10, 2016). "Creator Marc Brown on Mr. Rogers, Memes, and 20 Years of Arthur". Boston Magazine. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ King, pp. 353–354.

- ^ a b Santomero, Angela C. (September 21, 2012). "Mister Rogers Changed My Life". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2023. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ King, p. 353.

- ^ Owen, Rob (September 2, 2013). "A 'very Fred-ish' birthday for 'Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Pioneers of Television: Fred Rogers". PBS.org. 2014. Archived from the original on January 7, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Burns, Asia Simone (February 18, 2018). "Mister Rogers Still Lives In Your Neighborhood". NPR.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ King, p. 267.

- ^ a b Eberson, Sharon (March 17, 2019). "Fred Rogers re-emerges as champion for PBS". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Harris, Aisha (October 5, 2012). "Watch Mister Rogers Defend PBS In Front of the U.S. Senate". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Strachan, Maxwell (March 16, 2017). "The Best Argument For Saving Public Media Was Made By Mr. Rogers In 1969". HuffPost. Archived from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Approves 21 New State Historical Markers". PR Newswire. PR Newswire Association LLC. March 4, 2014. Archived from the original on June 2, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ "State Marker in Latrobe to Honor Mr. Rogers". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children's Media at Saint Vincent College. Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children's Media. March 5, 2014. Archived from the original on June 2, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Historical Marker Search". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Archived from the original on March 29, 2018. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ a b Gibson, Caitlin (August 12, 2019). "How Mister Rogers became a timeless oracle of parenting wisdom". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 18, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ McNary, Dave (November 20, 2019). "'Won't You Be My Neighbor', 'RBG' Nab Producers Guild Documentary Nominations". Variety. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- ^ a b "The Fred Rogers Collection – '51 '74H (1928–2003)". Rollins. Rollins College. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ "Public Media Awards: Ralph Lowell Award". Corporation for Public Broadcasting. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ "What's Happening: Thanksgiving Ball, Sewickley Event". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Vol. 51, no. 100. November 24, 1977. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Fanning, Win (May 2, 1977). "On the Air: CBS Drops 10 Shows; 'Two Men' to Debut". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Vol. 50, no. 235. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Among the Churches: Address By General Motors Minister To Highlight Salvation Army Week". The Pittsburgh Press. Vol. 93, no. 314. May 7, 1977. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Newell, David; Hamilton, Lisa Belcher. "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood Program Notes: Honorary Degrees Awarded to Fred Rogers". Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Family Communications, Inc. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ "Mister Rogers Gets Pitt Fraternity Honor". The Pittsburgh Press. Vol. 91, no. 216. January 29, 1978. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Fanning, Win (December 29, 1978). "On the Air: 'Supertrain' Has Super Set". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Vol. 52, no. 130. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Darovich, Donna (February 13, 1981). "Award-winning Rogers: kids' special-izer". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "Valley Viewing – Profiles in Excellence '82". The Morning Call. No. 29,352. June 16, 1982. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ a b "Distinguished Alumni". CINE. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ "Famous Sinfonians". Rock Hill, South Carolina: Nu Kappa Fraternity. Archived from the original on March 16, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "Mr. Fred Rogers Commencement Speech - Immaculata College 1988". YouTube. Immaculata University. May 15, 1988. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ "Commencement Highlights". Immaculata University. Immaculata News. November 24, 2019. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ "Vector awards". The Pittsburgh Press. Vol. 106, no. 165. December 7, 1989. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "PA Society To Honor Mr. Rogers". News-Herald. No. 109th Year – 5710. October 31, 1990. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Can you say…captain?". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Vol. 65, no. 58. October 7, 1991. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ Sal, Barry (March 21, 2016). "Mister Rogers' Hockey Card". Puck Junk. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ Hay, Bryan (May 31, 1992). "From Cardigan to Graduate's Gown Mister Fred Rogers Speaks at Moravian Baccalaureate". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ "Personal Award: Fred Rogers". Peabody Awards. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Sciullo, Maria (April 19, 2018). "2018 Peabody Awards honor The Fred Rogers Company". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ "Mr. Rogers, Heimlich among grad speakers". Press and Sun-Bulletin. Associated Press. May 15, 1994. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Evans, James H. Jr. (November 27, 2019). "Remembering Mr. Rogers' Rochester visit, and an important message". Democrat and Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 31, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "National Patrons & Patronesses". Delta Omicron. Archived from the original on March 17, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Fetters, Elizabeth Rusch, ed. (Spring 2018). "Mr. Rogers Golden Anniversary" (PDF). The Wheel: Educational Journal of Delta Omicron. 108 (1): 28. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ "Fred Rogers To Be Given Award In Pittsburgh". Latrobe Bulletin. Vol. 93, no. 45. February 11, 1995. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Fred Rogers Acceptance Speech - 1997". YouTube. The Emmy Awards. May 21, 1997. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ "TCA Awards". Television Critics Association. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Goodman, Tim (July 21, 1997). "'Bastard Out of Carolina' also tops TV award-winners". SFGate. Hearst Communications. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ "Fred Mister Rogers". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. October 25, 2019. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Owen, Rob (June 14, 2017). "Obituary: Jeffrey Erlanger / Quadriplegic who endeared himself to Mister Rogers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on September 30, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ "Ridge honors 'Mister Rogers' with award". Public Opinion. Associated Press. June 9, 1999. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Moranelli, Mandi L. (May 15, 2000). "Mister Rogers: Real Drama Of Life Not On Center Stage". Latrobe Bulletin. Vol. 98, no. 125. Latrobe Bulletin. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "The Buzz – Recognition". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Vol. 74, no. 208. February 24, 2001. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Mrs. Bush, Fred Rogers service award winners". Courier-Post. February 24, 2002. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipients". United States Senate. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ McFeatters, Ann (July 10, 2002). "Fred Rogers gets Presidential Medal of Freedom". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ "PNC Honors Six Achievers Who Enrich The World" (Press release). Wilmington, Delaware: PNC Media Room. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ "(26858) Misterrogers = 1952 SU = 1993 FR = 2000 EK107". IAU Minor Planet Center. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ "Asteroid is named after Mister Rogers". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. May 3, 2003. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ "Television Hall of Fame: Actors". Online Film & Television Association. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ "Television Hall of Fame: Productions". Online Film & Television Association. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ "Wear a sweater, honor Mr. Rogers". Today.com. Associated Press. February 27, 2008. Archived from the original on March 24, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ McCoy, Adrian (February 27, 2008). "Sweater day to honor Mister Rogers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Maloy, Brendan (June 11, 2015). "Minor league team honors Mr. Rogers with cardigan uniforms". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ "Mister Rogers Forever Stamp dedicated today". United States Postal Service. March 23, 2018. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ Hauser, Christine (February 13, 2018). "A Mister Rogers Postage Stamp, and a Legacy That's Anything but Make-Believe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ "Celebrating Mister Rogers". Google.com. September 21, 2018. Archived from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ Elassar, Alaa; Muaddi, Nadeem (September 21, 2018). "Today's Google Doodle is a heartwarming tribute to Mr. Rogers". CNN. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ "Here are the First Honors Announcements for 2019". Cinema Eye Honors. October 25, 2018. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Frieman, Jordan (March 14, 2021). "Grammys 2021: Complete list of winners and nominees". CBS News. Archived from the original on March 14, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Mister Rogers' Sweater". Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Lorando, Mark (June 19, 2017). "Mister Rogers to open a New Orleans neighborhood". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans, Louisiana. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ "Kids explore exhibit featuring Mister Rogers". WCAX.com. August 12, 2018. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ Hamill, Sean D. (March 16, 2010). "It's Still a Beautiful Day in His Neighborhood". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ McMarlin, Shirley (March 19, 2018). "New Mister Rogers 50th anniversary display opens March 20 at Heinz History Center". Trib Total Media. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.

- ^ "Heinz History Center". Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ "Visit the Exhibit". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children's Media. Archived from the original on May 31, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Visual Legacy". Pittsburgh Magazine. December 18, 2014. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 23, 2019.